MIT has revealed an ultrasound sticker that can offer medical workers a peek at a patient's internal organs without requiring them to use the bulky equipment they rely on today.

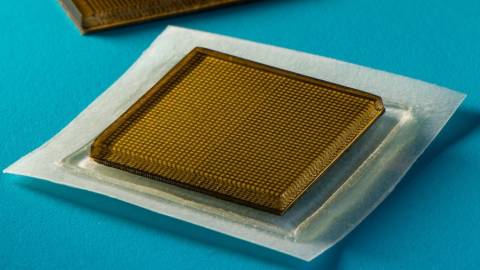

The university describes the ultrasound sticker as a stamp-sized device that sticks to skin and can provide continuous ultrasound imaging of internal organs for 48 hours. Experiments with these itty-bitty monitors showed that they were capable of producing live, high-resolution images of major blood vessels and deeper organs such as the heart, lungs, and stomach.

MIT says the goal is to create wearable imaging products that patients could take home from a doctor’s office or even buy at a pharmacy. The university isn't quite there yet, however.

The current version of the ultrasound sticker still has to be paired with a device that converts sound waves to images, MIT says. Its researchers have already started working on a wireless version that won't require patients to be physically connected to the other device, but until that version is available, people are unlikely to be able to use these ultrasound stickers at home.

The researchers aren't just working on wireless ultrasound stickers. MIT says they're also developing software algorithms based on artificial intelligence that can better interpret and diagnose the stickers’ images so they can be used not only to monitor various internal organs, but also the progression of tumors, as well as the development of fetuses in the womb.

Until then, MIT says the ultrasound sticker could have immediate applications even without these additional features. For instance, the devices could be applied to patients in the hospital, it says, similar to heart-monitoring EKG stickers, and could continuously image internal organs without requiring a technician to hold a probe in place for long periods of time.

More information is available in a paper that was published by Science on July 28.