Facebook News Feeds are largely customized based on users' social network and interests, but a new report on terrorist activity in East Africa contends that country and language play a bigger role in what people see than expected.

The platform relies on moderation algorithms to cull hate speech and violence, but the systems struggle to detect them in non-English posts, the Institute for Strategic Dialogue (ISD) says.

Two terrorist groups in Kenya—al-Shabaab and the Islamic State—exploit these content-moderation limitations to post recruitment propaganda and shocking videos, many of which are in Arabic, Somali, and Kiswahili.

“Language moderation gaps not only play into the hands of governments conducting human rights abuses or spreading hate speech, but are similarly resulting in brazenly open displays of support for terror groups,” the ISD report says.

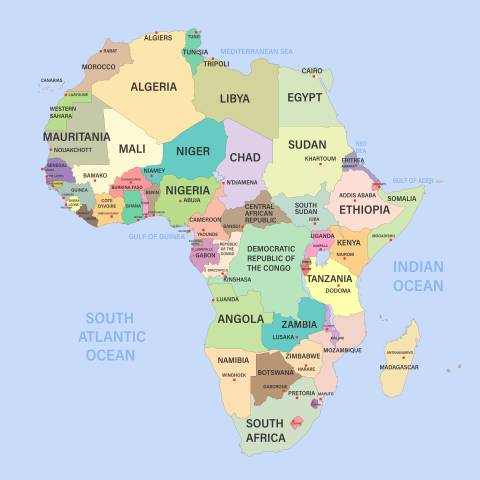

The report studied Facebook content posted in several East African countries, including Somalia, Ethiopia, Uganda, and Kenya.With elections coming up in Kenya on Aug. 9, the study cites 30 public Facebook pages from militant groups that intentionally sow distrust in democracy and the government. The most active al-Shabaab and Islamic State profiles are calling for violence and discord ahead of the election, and ultimately establishing an East African caliphate.

Meta, the parent company that owns Facebook and Instagram, has a team dedicated to monitoring platform abuses during Kenya's 2022 general election cycle. The team includes native Kenyans, and many speak Arabic, Somali, and Swahili.

Even so, the report found that a video posted on the official al-Shabaab page featuring a Somali man being shot in the back of the head was freely shared by five different users. The video was marked with recognizable al-Shabaab branding, which any content-moderation system operating in that region should be obligated to recognize. Out of 445 users posting in Arabic, Kiswahili, and Somali, all were able to freely share a mix of unofficial, official, and custom content clearly supporting al-Shabaab and the Islamic State.

An internal experiment conducted by Meta in 2019 showed similar results when creating a dummy account in India, The Washington Post reported last year. In a memo included in the Facebook Papers, a collection of internal documents made public by whistleblower Frances Haugen, Facebook employees reported being shocked by the soft-core porn, hate speech, and “staggering number of dead bodies” shown to a new user in India.

In contrast, the algorithm suggested a slew of innocuous posts to a new user in the US, a stark difference that illuminated the way the platform behaves for users in different countries.

Content-moderation gaps have the potential to negatively influence voter sentiment in favor of violent, extremist groups. The same happened in Myanmar in 2016-2018, where members of the military coordinated a hate speech campaign on Facebook targeting the mostly Muslim Rohingya minority group.

The posts encouraged a genocide of Rohingya people, which ultimately resulted in thousands of deaths and a global refugee crisis as at least 750,000 were forced to flee, The Guardian reported. In 2021, refugees in the US and the UK sued Facebook for spreading hate speech for $150 billion.

Meta contends that it's investing in systems to improve content moderation globally. ”We don't allow terrorist organizations to maintain a presence on Facebook, and we remove praise, substantive support, and representation of these organizations when we become aware of it, said a Meta spokesperson. We know these adversarial groups are continuously evolving their tactics to try and avoid detection by platforms, researchers and law enforcement. That’s why we continue to invest in people, technology, and partnerships to help our systems stay ahead.”

While moderating the world’s largest social media platform is an enormous challenge, the ISD report says identifying the content moderation gaps is a critical first step, including taking stock of the languages and images not detected by Meta's systems. Second, the report recommends bolstering the identification and removal of terrorist-specific content, particularly in countries with high risk of violence or election influences.

Finally, the ISD recommends not relying solely on Meta. The development of an independent content-moderation organization would aid tech companies in detecting gaps in moderation policies while helping them understanding the role they play in the regional ecosystem – beyond one specific group or platform. While Facebook is the hub of the dangerous activity, other applications such as Twitter and YouTube also play a role, the report found.

Individuals can also play a role by reporting dangerous content on Facebook and Instagram.

Editors' Note: This story was updated with comment from Meta.